I’m writing this post today from my local community centre pool, where my nine-and-a-half-year-old autistic son is taking his first-ever swimming lessons in a class format, unaccompanied. We’ve worked hard for this milestone!

Swimming lessons have been hard work for us.

We started when he was three years old. I knew swimming lessons were important for safety. I knew that other families had started lessons earlier than we did. Still, I was hesitant. My son had an unusual hyperactivity and lack of awareness that we didn’t quite have a name for yet. I also had an infant to take care of at the same time. Nonetheless, I faced my fear, signed up for an accompanied “Moms & Toddlers” swim class, strapped my infant into a baby carrier on my back, and hopped in the pool.

It was a colossal disaster. We made it through half a class before the lifeguards politely suggested that perhaps we should go down a level to the “Moms & Babies” accompanied class. So the very next day, I strapped my youngest to my back once again, and took my oldest into the water to participate in splashing and nursery rhyme games more suited to his baby brother. The entire thing was a worry and a workout. Every day for two weeks, the three of us darted around the pool in what must have been a comical sight.

At age four, we tried something new. Private lessons. I again went into the pool with the instructor, making it 2-on-1. The instructor was the swim expert, and I was the “expert” on the new word we had for my son: autism. She gave instructions, I communicated them in a way my son could understand, and we both kept him alive when he would dart away and jump into deep water, unaware that he could hurt himself. To my great surprise, he passed that level. “The biggest expectation for this class is just to get kids to jump into the pool,” she explained, “so every time he ran away and flung himself into the deep end was a check mark on my sheet!” The positivity of this girl was something else!

At age five, we tried something different once again. Class lessons with a personal helper. The pool suggested putting him into a regular class, and having a lifeguard in training assist my son as his personal aide in the water while the instructor focused on the other children. This plan quickly proved to be too ambitious. The noise and distraction of other children in the water was too much. My son panicked and screamed and fought his trainee helper. Back to the drawing board.

At age eight after a Covid-19 break, we decided to go back to what was working: 1-on-1 with Mom. Our pool had another suggestion for us. This time it worked wonderfully. The pool hosted a disability-friendly water aerobics class each week. While this was happening in the shallow end, the deep end and the kiddie pool were empty. They invited Special Olympics families to make use of these areas at that time for free. It was amazing! Together, we worked on water safety, floating, and dog-paddling with a life jacket on. My son’s abilities grew by leaps and bounds as he worked at his own pace, and was cheered on by his friends. On our family vacation that summer, he impressed us all with his confidence and carefulness at the beach.

This spring, he sat poolside with me while his little brother–now fully outgrown his baby carrier–took his swimming lessons. I couldn’t help but notice how interested he was, and asked him about it.

“He do a class too?” he said, poking himself in the chest.

“You want to try a class?” I answered back. “Do you think you can do a class with other kids and just one teacher like that? Will you be a good listener?”

“Yes. I will do the class,” he nodded confidently.

So here we are. Nine and a half years old. Level One. He’s several years older and several inches taller than his classmates, and he’s behind his little brother’s level. He doesn’t care. On his first day, his instructor tossed sinking rings into the pool and asked the class to pick them up. He dunked down and came up holding a red ring in a superhero pose. “Nailed it!” he shouted, for all the pool to hear. The years of stress have all been worth it.

You may be wondering, “why work so hard and stress so much over an extracurricular activity?”

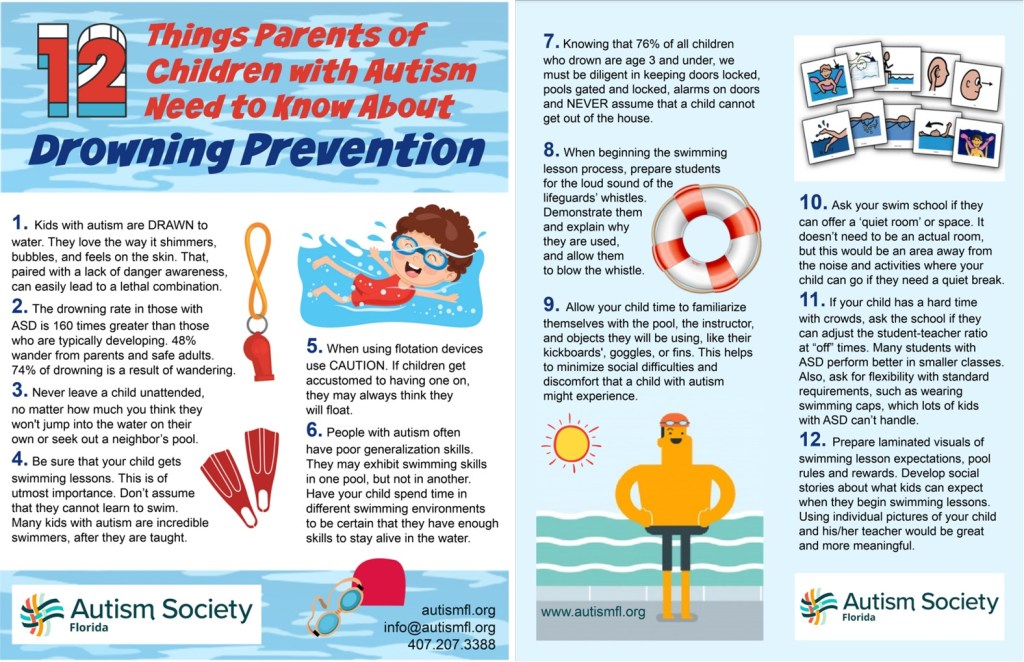

A study in 2020 found that autistic children are three times more likely to drown than their neurotypical peers. And a study done between 2009 and 2011 found that 91% of autistic child deaths are caused by accidental drowning. Water safety is serious business in autism families.

There are a number of reasons why drowning is the leading cause of death in autistic children. For starters, water is very appealing to a sensory-seeker. It shimmers, and moves beautifully. It’s calming to watch. The coolness and warmness of the water is a wonderful sensory experience. Most autistic children are mesmerized by water and drawn to it.

Another reason, is that autistic children are typically “runners.” The official term for this phenomenon is “elopement.” I’m sure you hear the word “elope” and think of a happy couple in love running away to get married. Well, that’s pretty much the correct mental image… just replace in your mind the happy couple with a small child, the love with intense fascination, and the destination of a wedding chapel with the location of the child’s current fixation.

Autistic children can develop a one-track-mind sort of obsession with things, and can disappear in an instant, following the object of their desire. They don’t mean to “run away,” they are just completely caught up in the moment. 48% of autistic children elope into dangerous situations. The leading dangerous situation is unattended bodies of water.

Another reason drowning is so prevalent among autistic children, is an underdeveloped sense of critical thinking and sense of safety/danger. Autistic children think in patterns. If their only experience with water is the bathtub, they will automatically assume that all water will be as shallow and safe as a bathtub. If they are only ever allowed to swim with a life jacket on, they will automatically assume that they will always float in water, not realizing that the life jacket has anything to do with it.

The Autism Society of Florida has developed these great posters about autism and water safety that are worth the read. They are available to download and print on their website.

If you reside in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada, as I do, you should know that there is now a grant available to help you pay for your autistic child’s swimming lessons.

Saskatchewan has a fund for families with autistic children under the age of 11 years. If your child has an official medical diagnosis of autism, you can apply for funds to help with important interventions for your child, including speech therapy and occupational therapy. Recently, the program announced that swimming lessons have been added as an eligible expense, in recognition of just how important water safety is for our little ones.

If you are interested in learning more about this Government of Saskatchewan program, click here: Saskatchewan Autism Services.

© 2023 Ashley Lilley – First time commenting? Please read my Comment Policy.

Discover more from Ashley Lilley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You are such a boss! Seriously you impress me with your patience, your hard work and your commitment to help your kids be the best they can be. Kudos to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw, thank you so much!

LikeLike

You, my dear, are a great mom. Our youngest is in the autism spectrum, though it wasn’t diagnosed until young adulthood. I recall many times when our kid would “run off” and I always chalked it up to ADD, which they were diagnosed with at age 8. But now I see it was the autism. They would just get fixated on one single thing and didn’t have the ability to physically stop themselves from persuing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Rhonda. It sounds like your youngest is safe and sound, so you are a great Mom too. Well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting post. I myself have a 15-year-old boy with autism. We are trying to teach him to ride a bike now. He has two nice girls who work as caregivers who will ride with him. The caregivers have a tricycle for adults that we can borrow. But when the caregivers want to put on a bicycle helmet and a visible vest, he can get very angry and disappointed. The challenge right now is to try to get him to understand that he should use a helmet and vest when he rides a bike.

LikeLike

That’s so challenging! It seems a cruel irony that the people who need safety gear the most, are usually unable to wear it due to sensory sensitivities. Vests, helmets, lifejackets, closed-toed shoes, sunscreen… It’s. All. Sensory. Best wishes to you and your son, Becky.

LikeLike